Part I: The War

There is no column for race in the Dix Hospital admission records during the period of our digitization project (1856-1921). This archival absence is intentional and speaks volumes about the effects of white supremacy in North Carolina and the South more generally. In records of all kinds, whiteness is assumed and unmarked; Blackness is assigned and marked. However, there is a momentary exception that proves this race rule: between 1865 and 1880 some forty-seven individuals are labeled as “African” or “colored” in parentheses beside their names in the admissions ledgers. And then the unarticulated regime of whiteness is restored across the nearly four decades and thousands of subsequent records to which we had access. Indeed, there is reason to believe that the elision in the records and the exclusion it signified extends to the mid-1960s, when state institutions were required by law to “integrate.”

There is but one book-length history of Dix Hospital: Marjorie O’Rorke’s Haven on the Hill: A History of North Carolina’s Dorothea Dix Hospital (N.C. Office of Archives and History, 2010). With extensive experience as a medical/surgical nurse and a long-time volunteer at Dix Hospital, O’Rorke has provided a very useful administrative account of the hospital’s operation from the 1960s through the controversial decision to close the hospital in the early 2000s.

The nineteenth-century history of the hospital, however, receives much less attention: forty pages out of 240. The presence of African American patients in the hospital between 1856 and 1880 is covered in two paragraphs (p. 16), and they deal entirely with the immediate post-Civil War period from April 1865 to November 1866. The first African American patient is not identified by name, (whom we now know as Isaac, who appears at the bottom left of this image) but merely as “a soldier,” who was admitted on April 13, 1865, by order of federal provost marshal, when Union troops were still occupying the site. The first female African American patient (whom we now know as Priscilla), admitted a month later, is described as “a Raleigh woman.”

At the beginning of the spring term of 2020, participants in my graduate research seminar were eager to explore the relationship between race and the asylum—at Dix and in the development of modern psychiatry. Our first task was to make the racial presence/absence dichotomy “visible” in the records, and, through them, in the institutional policies of the hospital. We transcribed the scant information from the admissions ledgers and entered it into a spreadsheet.

The outbreak of COVID in March 2020 disrupted these plans. However, the seminar’s accomplishments deserve recognition: they had recovered from the archive and, for the first time, “spoken” the names and identities of African Americans in what was then the state’s only insane asylum. In early May, American Studies PhD candidate Anna Hamilton pointed to the case studies their work might make possible. She wrote on the course website:

Sharing these stories of Black patients at Dix beckons us inside the asylum walls, offering insights into the treatment of African American mental health in the South at a precarious period in the nation’s history. We leave this for readers and future scholars to pick up where we left off.

Only a few weeks after the semester ended, however, the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, connected that historical period of systemic racial violence and social injustice with the present.

That summer, I started searching for evidence of the lives of these individuals in the digitized resources available through Ancestry.com and its subsidiary sites Newspapers.com and Fold3, hoping to find at least one African American committed to Dix for whom a life history during and after slavery might be pieced together.

I was inspired by Bernetiae Reed, our collaborator on the Rocky Mount Mills project. Having compiled a four-volume history of Thomas Jefferson’s slaves, she has worked for years to recover the history of her own family, some of whom were enslaved by members of the Battle family, which owned and operated Rock Mount Mills. She was a key resource in organizing a slave genealogy workshop at the renovated mill in 2018.

Then, on January 18, 2021, the American Psychiatric Association published on its website an “Apology to Black, Indigenous and People of Color for Its Support of Structural Racism in Psychiatry.”

Today, the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the oldest national physician association in the country, is taking an important step in addressing racism in psychiatry. The APA is beginning the process of making amends for both the direct and indirect acts of racism in psychiatry. The APA Board of Trustees (BOT) apologizes to its members, patients, their families, and the public for enabling discriminatory and prejudicial actions within the APA and racist practices in psychiatric treatment for Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC). The APA is committed to identifying, understanding, and rectifying our past injustices, as well as developing anti-racist policies that promote equity in mental health for all.

This legacy of discrimination reached back to the formation of psychiatry as a profession and medical specialty in the 1840s. It was manifested in the actions and practices of the first generation of American psychiatrists: the superintendents of dozens of public and private insane asylums created between the 1820s and the 1850s. The practices included “abusive treatment, “experimentation,” and “victimization in the name of ‘scientific evidence.” Such abhorrent actions undertaken by individual doctors continued to inform the development of psychiatry in the twentieth century, leading to racial discrepancies in access to care, diagnosis, and treatment. The apology extended to the silence and inaction of the APA, which contributed to “perpetuation of structural racism that has adversely impacted not just its own BIPOC members, but psychiatric patients across America.”

The APA apology admits the profession’s failure to reckon with its own history and points to the nineteenth-century American asylum as the place to start in coming to terms with the legacy of past injustices. It relocates race from the margins of the history of psychiatry to the center.

Finding Eli Hill

Even in the best of research circumstances, recovering the identities and lives of former slaves in the South is a formidable challenge. Most slaves did not have surnames—indeed one of the first acts of personal agency for many freed slaves was to choose a surname for themselves and their children. Many were forbidden to learn how to read and write. Slaves could not legally marry. Family units under slavery were routinely subject to traumatic dissolution and separation.

One of the very few details of the story of African American presence at Dix (and one that is invariably mentioned in public accounts) is that the first admission in April 1865 came about as a result of Union forces occupying the site of the hospital when the war ended. The Dix Park Legacy Committee’s 2018 report notes: “The presence of Union troops also changed Dix Hospital, as hospital officials were ordered to accept their first African American patient—Isaac, a soldier, admitted because of “the War” on April 13th. Another was admitted because of “Emancipation.” By October 1865, the hospital had admitted 10 more black patients.”

The report mentions one other African American patient, again in the context of the Civil War. In a brief discussion of the Dix Hospital Cemetery, it notes: “With more than 950 people buried there, it is a beautiful site at the top of the hill. For example, Eli Hill was one of those buried there in 1877. Hill had been enslaved, joined the Colored Troops of Gen. Sherman, returned to N.C. as a patient at Dix, and died there.” (p. 16-17)

All we learn from the admissions ledgers is that Eli Hill was admitted on January 27, 1870; the notation “(colored)” written beside his name. His age is listed as 25 years, his occupation as laborer. He was from Onslow County. He was a patient at Dix until his death in 1877.

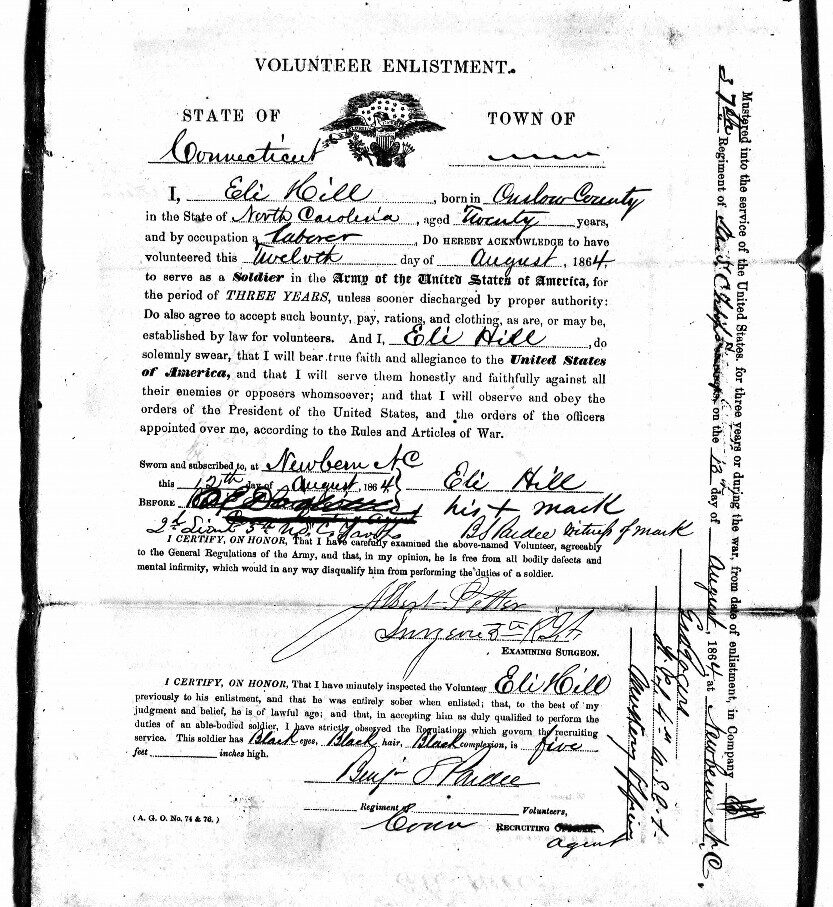

Indeed, it was Hill’s service as a soldier in the U.S. Colored Troops that made possible a fuller account of his life. Ancestry.com’s military history resource, Fold3, contains the compiled service records of those who fought on both sides of the conflict: Confederate, Union, and U.S. Colored Troops. Perhaps the most valuable of the service records are muster roll cards, which allow us to follow soldiers’ lives at monthly intervals from their enlistment to their death or discharge. The spring 2020 graduate research seminar had discovered Hill’s service records. By the end of the term, Savannah Foreman had drafted a blog post demonstrating how they might be used as a teaching resource.

In the spring of 1863, the U.S. War Department began recruiting African Americans for what became known as the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Some 175 regiments, more than 178,000 freed slaves and free persons of color, served during the last two years of armed conflict, more than 5,000 of them from North Carolina. Eli was one of thousands of escaped slaves in eastern North Carolina who fled farms and plantations for New Bern, which was under the control of Union forces early in the conflict. This made New Bern a prime Union army recruitment center for free persons of color and escaped slaves. In August 1864, he joined Company F of the 37th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops. Recruiters, who earned a fee for each enlistment, competed against each other. The inducements were several: enlistees received pay (although less than that received by white soldiers), support for their families, and, by 1864 a recruitment bounty.

The decision to enlist would not necessarily have been an easy one for these men. In addition to the possibility of injury, disease, capture, and death faced by all soldiers, members of the U.S. Colored Troops faced particular threats. In a place like North Carolina, capture could mean that they would be returned to slavery or pressed into labor gangs. There might be reprisals against their families. There were stories of Confederate officers adopting a “no prisoners, no quarter” policy against African American troops. We do not know Eli Hill’s motives for joining the U.S. Colored Troops in the summer of 1864, nor do we know the family he might have left behind.

Richard Reid’s book, Freedom for Themselves: North Carolina’s Black Soldiers in the Civil War Era (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2014), is a detailed history of the three regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops raised in North Carolina, including the 37th Regiment, in which Eli served from 1864 to 1867. The circumstances of his service provide insights into the military role of freed slaves and free persons of color in North Carolina during and after the war.

What more can we discover about Hill’s military experience? A notation on a muster roll card from the fall of 1864 indicates that he was a “musician.” Drum Corps were a part of every unit in the Civil War. Every company had at least two musicians: a drummer and someone who played the fife or the bugle. In all there were some 40,000 field musicians, many of whom were under the age of sixteen. Indeed, boys as young as twelve could enlist as drummer boys if their parents approved. Eli was twenty at the time of his enlistment in 1864. Drum corps played a key communication role in each company every day.

On the battlefield, drummer boys served as stretcher bearers and medics. After the battle, they removed the dying and dead. Historian Eric Dean’s Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1999) provides a terrible litany of the mental and physical traumas soldiers on both sides of the conflict endured: homesickness, the prospect of being ordered to kill other men, the very real fear of death or mutilation at any minute. Constant bombardment by heavy artillery reduced men to mutism and uncontrollable shaking. In between battles there was constant discomfort: the fatigue of forced marches in all weather, followed by nightly exposure sleeping on the ground with only a sodden blanket for protection.

Hill joined the last of the four regiments of U.S. Colored Troops raised in North Carolina. The actions of military units in the Civil War—down to the level of the company—are well-documented, so we have a pretty good idea where Eli Hill was every month of his service and what combat actions he might have been involved with.

Soon after enlisting in New Bern, North Carolina, on August 13, 1864, he joined his unit in Virginia as part of what was called the “Army of the James”: combined Union forces that attacked Confederate positions in the area between Richard and Petersburg between June 1864 and March 1865 in an attempt to destroy key transportation hubs.

He would have experienced combat throughout the fall of 1864 along the James River, including the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Heights (September 28-29), at which units of U. S. Colored Troops distinguished themselves, one of them, Christian Fleetwood, eventually being awarded the Medal of Honor. There were some total 5000 casualties in the inconclusive engagement around Chaffin’s Farms. A month later, the 37th Regiment was a part of General Benjamin Butler’s unsuccessful attack on Confederate defenses around Richmond at Fair Oaks on October 27 and 28th. Some 600 Union troops were captured and more than 1600 wounded or killed. From that point until the end of the war, both sides settled into trench warfare as Union forces besieged Petersburg.

In early December, Hill’s regiment was assigned to an ambitious amphibious expedition to take Fort Fisher, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, which protected the city of Wilmington, North Carolina. Troops would be transported by sea from Hampton Roads, Virginia, accompanied by some sixty naval vessels. Embarkation was set for December 10, but winter storms delayed the voyage for thousands of troops, including Hill, for some three weeks, confining them to cramped quarters in the holds of heaving vessels. Miscommunication and dithering among Union Generals doomed the expedition. Troops were returned to Hampton Roads, and General Butler was relieved of his duties by President Lincoln.

It is around this time—January 1865—that muster roll cards show Hill as being “absent sick” and in hospital. It is not known what he was suffering from. Had he been injured in battle, he would have been listed as “wounded” rather than sick.

Dean calls the conflict a kind of biological warfare: for every combat death there were two from disease: cholera, typhoid, malaria, yellow fever, smallpox, measles, mumps, scurvy, diphtheria, dysentery, tuberculosis. Three quarters of all troops contracted these or other serious diseases annually. When soldiers were injured or succumbed to disease they were treated by doctors using germ-infested instruments and few effective medicinal remedies. Opium was routinely used to kill pain or control diarrhea. Calomel (a form of mercury) was given as a purgative.

By late February, Hill had been returned to active duty and was back to within sixty miles of Onslow County, North Carolina, the place from which he had escaped in the summer of 1864. His regiment participated in the capture of Wilmington on February 22nd. It then joined in what has been called the “Carolinas’ Campaign”: the mass mobilization of Union forces under General William T. Sherman to sweep north across South Carolina and North Carolina with the goal of joining Union forces in Virginia. Hill would have participated in the capture of the key rail hub in Goldsboro (March 21) and the advance on Raleigh in early April, leading eventually to General Joseph Johnston’s surrender at Bennett Place on April 26 and the end of hostilities in the Carolinas.

Hill might have been part of the Union forces that captured Raleigh on April 13, 1865, and among the U.S. Colored Troops who paraded in review before General Sherman on April 20. We know that Isaac, the first African American patient at Dix, did not participate in the celebratory parade: he had been admitted to Dix Hospital on April 18—the supposed cause of his attack of insanity was listed as “the war.”

Read the rest of Eli’s story here.