Our work has been inspired by the American Psychiatric Association’s “Apology to Black, Indigenous and People of Color for Its Support of Structural Racism in Psychiatry,” published in January 2020. It acknowledges a legacy of “prejudicial actions” and “racist practices” in the treatment of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color that reaches back to the formation of psychiatry in the 1840s and to the practices of the first generation of American psychiatrists: the superintendents of dozens of public and private insane asylums created between the 1820s and the 1850s. This legacy includes not only individual “abhorrent actions,” but also institutional silences and systematic exclusions.

We believe that the long history of mental illness and mental health treatment in North Carolina cannot be responsibly represented except in the context of race, and that the history of race in North Carolina encompasses Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

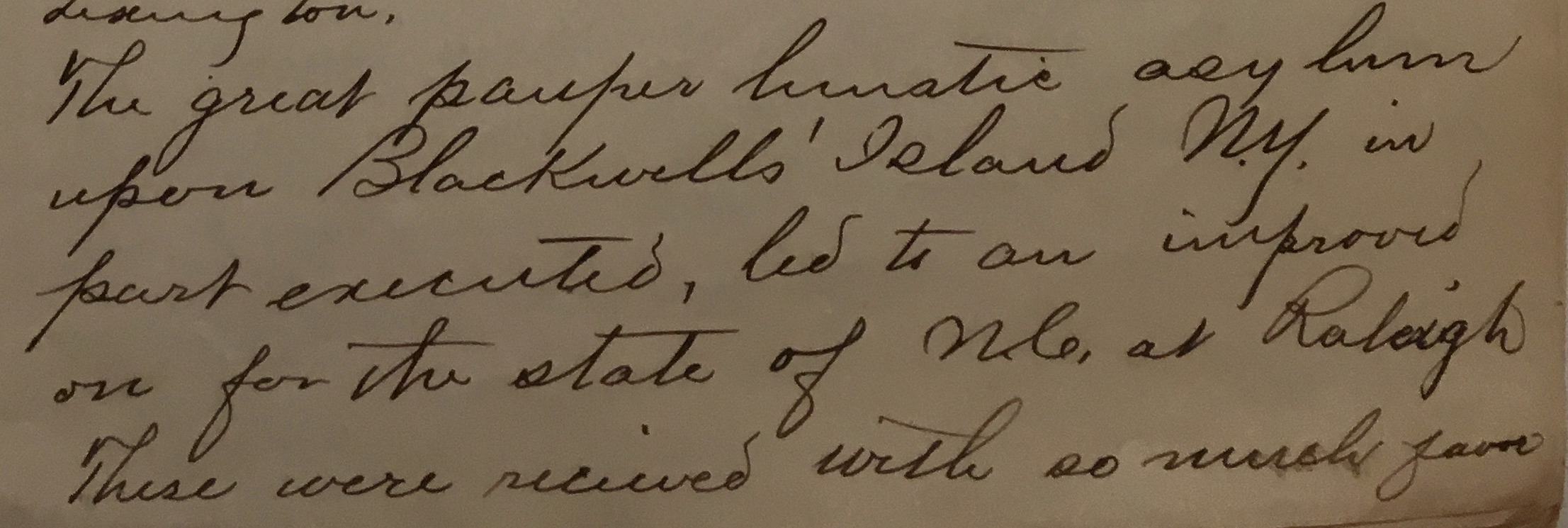

The only time race explicitly appears in the admissions ledgers is the notation of a small group of patients noted as “African” or “colored” (see image below), who were admitted between 1865 and 1880. Then, once again, we were confronted by the absence of any racial designation across the nearly four decades and thousands of subsequent records to which we had access. However, the relationship between race and the asylum in North Carolina in the nineteenth and early twentieth century is not just one of exclusion from Dix: in 1880 the state opened an asylum exclusively for African Americans. What became Cherry Hospital in Goldsboro served that function until its integration in 1965.

The first task was to make this presence/absence dichotomy “visible” in the records, and, through them, in the institutional policies of the hospital. This task was accomplished by AMST 715 graduate research seminar participants in the spring of 2020. They transcribed the scant information from the admissions ledger and entered it into a spreadsheet.

And then, in early March, COVID disrupted everything. The seminar members persisted however, and by the end of that semester, we could name forty-seven African American inmates out of more than 7,000 admissions between 1856 and 1918. Further, we could project that these were the only individuals identified as African American to have been admitted to the hospital until its racial “integration” in the mid-1960s. Again, this is a signal accomplishment. Had it not been for the liberalization of the state open records law in 2016, our commitment to transcribe and digitize them, and intrepid scholars who would not be cowed by a pandemic, these lives might have been indefinitely forgotten.

In late April 2020, one of the seminar participants wrote on behalf of her colleagues on the class website: “Sharing these stories of Black patients at Dix beckons us inside the asylum walls, offering insights into the treatment of African American mental health in the South at a precarious period in the nation’s history. We leave this for readers and future scholars to pick up where we left off.”

When this text was drafted, “precarious period in the nation’s history” referred to the aftermath of the Civil War. A few weeks later, the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, connected that historical period of systemic racial violence and social injustice with the present. Over the year since, we have continued to search for records—inside and outside the archive–that might illuminate the relationship between race and the asylum. Our immediate goal was to find one person about whom we might piece together the outlines of a life, particularly one that spans the experience of slavery and the experience of the asylum.

Even in the best of research circumstances, recovering the identities and lives of former slaves in the South is a formidable challenge. Most slaves did not have surnames—indeed one of the first acts of personal agency for many freed slaves was to choose a surname for themselves and their children. Many were forbidden to learn how to read and write. Slaves could not legally marry. Family units under slavery were routinely subject to traumatic dissolution and separation.

But thanks to Civil War service records compiled by Ancestry’s military history site, Fold3, we were able to find Eli Hill. He was admitted on January 27, 1870; the notation “(colored)” written beside his name. His age is listed as twenty-five years, and his occupation as laborer. He was from Onslow County. He was a patient at Dix until his death in 1877. He is “visible” in the archive only because he was a soldier in the U.S. Colored Troops of the Union Army. His military service was documented in his compiled service records preserved by the National Archives and Records Administration.

We continue to work on Eli Hill’s biography, unfolding this singular case study as a reflection on the construction of race in early psychiatry, the experience of African American soldiers in the Civil War, the plight of African Americans during Reconstruction, and unstable racial categorization in North Carolina.

Indigeneity in the Asylum & Archive

Too often, studies of race and the asylum, particularly in the South, are rendered in color-coded binary terms. This practice is particularly problematic in North Carolina, which is home to the largest tribal community east of the Mississippi, the Lumbee of southeastern North Carolina. In her new book, Committed: Remembering Native Kinship In and Beyond Institutions (UNC Press, 2021), CHW Visiting Scholar Susan Burch reframes the relationship between race and the institution of the asylum by focusing on the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians in South Dakota (1902-1935) and the network of institutions of “removal and confinement” As she argues, the history of indigenous peoples’ confinement in insane asylums is “inextricably tied to broader stories of Native self-determination, kinship, institutionalization, and remembering.” Her book is built around what she calls “microhistories”: the focused study of personal lives. These stories are, she readily admits, “messy and incomplete,” but “their disorderliness is not without meaning or purpose.” They have the power to “create, challenge, maintain, shape shift, and destroy” (p. 2).

During spring term 2021, Professor Burch participated in our graduate research seminar and presented a talk on her research for a webinar, attended by more than sixty scholars around the U.S. and abroad. Professor Dan Cobb, Director of the American Indian Studies program at UNC, contributed a response and moderated discussion.

Her work has encouraged us to ask how American Indians have been placed and displaced in relation to North Carolina’s asylums since 1856, and how this relationship has been obscured in the archive and in historical accounts. As noted, the Dix Hospital admissions records do not include fields for race. (The notation of “colored” or “African” for the forty-seven African American inmates is added in parentheses beside their names.)

We are taking first steps toward documenting this complex and dynamic relationship, evidence for which lies largely outside available asylum admissions records.