At the beginning of her examination, Mrs. Jones is asked by Dr. Anderson to tell the medical staff if there was anything the matter with her. She asks if he wants her to tell them “what I was brought here for?” Her reply: I was brought her for imagination, but some things, I don’t think I imagined.”

She talks about suffering “a great deal with pain,” but being told by Dr. Sadler, a local physician, that she “imagined all of these things.” Dr. Anderson asks if that was the reason she was sent to Dix. “Yes sir,” she replies. He asks again, “Was it your imagination?” This time she responds by telling the doctors that she had never been a strong and healthy woman.

She relates being treated by a local doctor and being told that if she did not stop worrying she would “lose her mind.”

A minister’s warning that if she died she would go “straight to torment” adds to her worries—“this fix”—she calls it—part of which “is imagination and part of it is not.”

She then talks about an “awful pressing in my head,” which a doctor tells her is caused by high blood pressure.

Dr. Anderson asks her about her imagination in relation to the birth of her last child and whether she imagined “any of these things” before the baby was born. She replies: “I didn’t imagine any of these things I just told you before the baby was born it was afterwards.” “I know everything that goes on, but seems like it is a strain on me, and I remember everything.”

Imagination is an important term–a privileged signifier, we might say–in Mrs. Jones’s examination. It is the word she chooses as the reason she understands she was brought to Dix, one that goes unchallenged and re-used by Dr. Anderson. It is used to invalidate her experience of pain by another doctor. It is associated with both religion and the experience of childbirth. But what does it signify and to whom in this case?

Looking at the uses of the term in newspapers around the time of Mrs. Jones’s admission to Dix we can see that by the late 1910s its meanings were varied and shifting. It is used as a kind of abstract reasoning as in: “I imagined several days more would elapse before they would search for us” (1915); or “It can be well imagined we had no time to waste” (1915). It can suggest the construction of mental images, as in her “imagined her. . .wandering homelessly in her desolate country” (1917). Advertisers used it as a projection screen of desire: “Haven’t you sometimes in imagination seen yourself spinning along with a party of friends in your own auto?” (1917) It is teamed with or substituted for “vision” to mean the mechanism by which a possible future can be posited: “Have imagination, have some vision.” (1917) It is distinguished from mere fancy or idle wondering: “Do you know the difference between imagination and daydreaming? Imagination has to do with the conscious side of your mind—it connects your mind with the world and so helps you in relation to people and incidents that you necessarily have to deal with.” (1917).

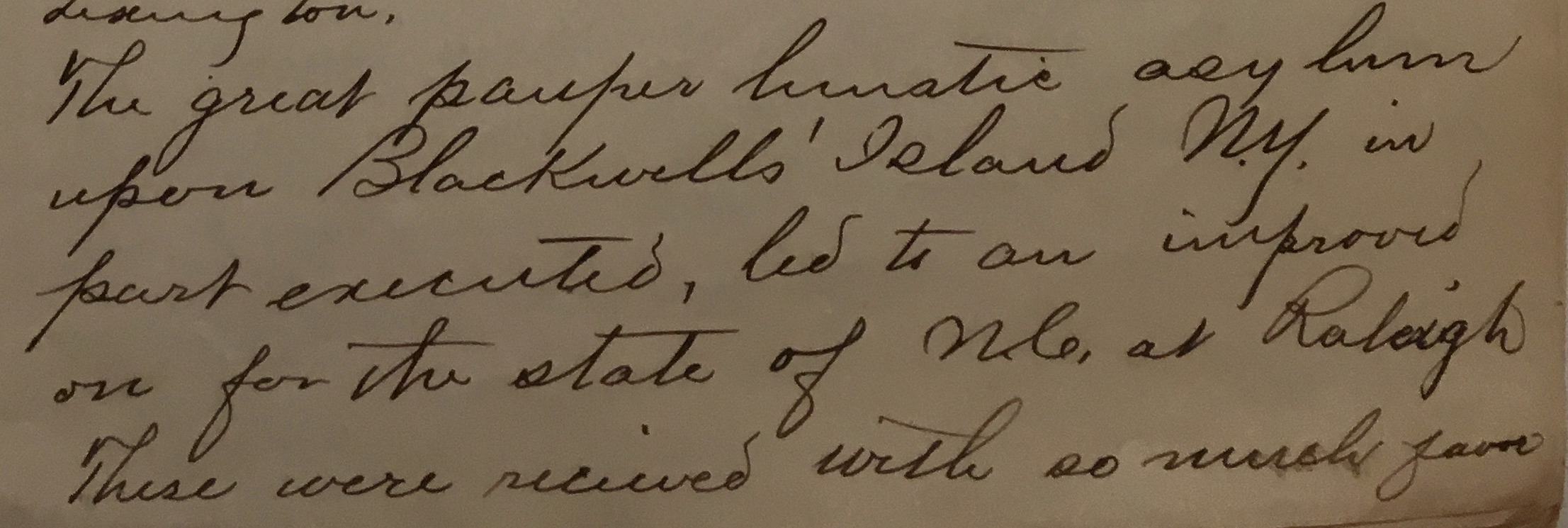

Imagination can be used as a mode of apperception unavailable to the stubbornly empirical and literal. “What reason is to faith,” one commentator wrote, “matter-of-fact is to imagination.” (1917) Indeed, imagination was touted as a psychological quality to be cultivated. In 1920, Dr. Edwin Mims of Vanderbilt University toured North Carolina with his talk, “Imagination and Creative Thinking.” At a talk given at Asheville High School he declares, “Imagination is not opposed to reality,” but rather the greatest realities spring from imagination. Reason and imagination join to produce the great intuitions which are beyond all realm of logic. (Asheville Citizen Times, July 9, 1920)

However, the term is also used to mean an idiosyncratic conception or belief that has no basis in the external world. A newspaper headline from 1917 proclaims: “One’s Troubles Frequently Will Be Found to Exist Only in the Imagination.” This is certainly one of the meanings of the term at play in the examination, but here it is applied to bodily and mental sensation, particularly pain. We don’t know if this is a term Mrs. Jones adopts from Dr. Sadler’s telling her she imagined “all these things,” but it is this disjuncture between her sensations and the doctor’s inability or refusal to acknowledge them as medical symptoms that seems to have precipitated her being committed to an insane asylum.

It is useful at this point to compare the interview with the general case book entry for Mrs. Jones, recorded (we can presume) on or near the date of her admission: January 28, 1917. Several things stand out. The supposed cause of her attack of insanity is listed as “child birth and heredity,” and the duration of the present attack as “about six weeks.” Under “first manifestations” are “Talks Continually, Will not sleep, Does not notice children,” and the second manifestations as “same.”

Beside “Delusions and Character of Same” is noted: “Thinks she has all sorts of diseases. Beside “Illusions and Hallucinations” is a dash, which could stand for “none” or a repetition of the response to the item above. The form describes Mrs. Jones as not being homicidal, violent, suicidal, or suspicious of friends or others. She has a good memory for recent and remote events, has “self-knowledge” of her mental condition, and is trustworthy. The source of information for this description is listed as her commitment papers.

Although the noun “imagination” is not used in the general case book forms, it is clear that its verb form “imagine/imagined” is a general synonym for “delusion” and (less frequently) for “hallucination.” It is also used to describe manifestations. In the field for first manifestation patient 7359 is described as “very nervous and imagines he is all to pieces inside.” Under delusions is noted “Thinks he is all to pieces inside.” Patient 6908 “imagines she has all kinds of diseases;” and patient 6782 “imagines she is bewitched, that she is in fire.” Imagine is used to characterize auditory or visual phenomena. Patient 7237 “imagines she can see and talk with mother.”

For her 1993 article in the journal Signs (“Women’s Voices in Nineteenth Century Medical Discourse: A Step Toward Deconstructing Science”), historian Nancy Theriot examined medical case notes, asylum admissions ledgers, and insanity commission records for women deemed to be insane in nineteenth-century Britain with the goal of finding instances in which the “voices” of these individuals might register. She concludes that in order to “hear” these voices, the historian must “listen” for the way in which disease is constructed through the interaction of discourses. She makes a distinction between illness and disease. Illness is a “self-defined state of less than optimal health.” As we have seen in the case of Mrs. Jones, illness is experienced and characterized in relation to personal history, physiology, and interpersonal relationships. Disease, on the other hand, is the construction of a categorical representation of individual illness in terms of symptoms (signs), causation, and cure. Doctors asked women to describe what they were feeling, and then translated these reports into disease symptoms. By the end of the nineteenth century, the professional representation of women’s mental illness involved discursive “border disputes” among three emerging medical specialties: gynecology, neurology, and psychiatry.

Theriot also identifies another voice that contributed to the negotiation between individual illness and disease, and one we can hear in the general case book forms: that of family and friends. Mothers, husbands, daughters, sons, in-laws and friends were often important intermediaries between women and local doctors, lunacy commissions, and insane asylums or sanitoriums. They took women to seek medical advice in hopes of explaining and treating disturbing behaviors, beliefs, or physical conditions. They could initiate and give evidence before county-level lunacy commission inquiries into anyone in the community, leading to that person’s being declared legally insane and being involuntarily committed to a state facility. The general case book form gives us information on patients’ families, their “correspondents” (who should be contacted in the event of the patient’s death), and who brought the patient to the hospital at the time of admission.

The very last field on the form is labeled “Source of Information”—that is, who or what supplied the information upon which the record was based. The most common sources in addition to the patient were the commitment papers (usually noted as “Com. Pap.”), but others who provided information about the patient (and who presumably were interviewed at the time of admission) included county sheriffs, local doctors, friends, and relatives (including husbands, wives, mothers, sons, sisters, brothers, daughters, and cousins) and occasionally a nurse or attendant at a facility from which the patient was transferred (as was the case with Mrs. Jones).

By October of 1916 whoever was filling out the form simply noted “Com. Pap. and History” on many records, leading us to wonder whose version of the patient’s history was relied upon. Reading through the manifestations, delusions, and hallucinations, it is clear that in many cases these are things being ascribed to the patient not by a doctor or the staff member filling out the form, but by other people in the patient’s life, in terms that reflect their social and cultural values; norms of aberrant behavior, belief, and ideation; understandings of the body and illness; personal history with and feelings about the patient; and, ultimately, their conceptions of the causes, symptoms, and effects of insanity. We can only imagine the scene, in a performative sense, that played out every day that a patient was admitted—who the actors were, what relationships were involved, what stories they told. Were the patients allowed to tell their own stories or to contest the version someone else told? Who was believed? Ultimately, the strands of whatever stories were told were brought together as evidence of insanity and a title given to the play: the supposed cause.