Minds may know and be known by cognitions. But persons are enacted rather than known, enacted by performances with a story in mind.

William Frank Monroe, Warren Lee Holleman, and Marsha Cline Holleman, “Is There a Person in this Case?” Literature and Medicine 11:1 (Sp. 1992): 45-63

In 1916, Dix Hospital superintendent Albert Anderson (1913-1932) instituted the minuting of regular medical staff meetings, and the verbatim transcription of brief staff interviews with some patients, most of whom had been admitted in the previous 30-60 days. Typescripts from the period 1916-1918 survive and have been digitized by the Community Histories Workshop. The purpose of these brief “examinations,” as they were called, was not to declare someone insane or commit them to a psychiatric facility. This had already been done at the county level by a “lunacy commission.” Rather, answers to the assembled doctors’ questions provided a basis upon which a staff doctor’s provisional diagnosis made at the time of admission could be confirmed, contested, or deferred. The superintendent had the final word.

The interviews represent the only surviving records in which the “voice” of those committed to Dix in the early twentieth century can be heard. However, they cannot be understood apart from the existentially asymmetrical power relations that underwrote exchanges between asylum doctors and hospital inmates. In form, they are much more interrogative than therapeutic.

As a part of the spring term 2022 Asylum in the Archive practicum, Irmak Saklayici (Health Humanities) and Zoe Schwandt (Anthropology) focused on (1) making the collection of more than one hundred interviews machine-readable and searchable, and (2) providing a guide for interdisciplinary historical analysis. This project was supported by Emma Stout and Nate Nihart (SILS). We look forward to engaging scholars from a range of disciplines and professional orientations with these records.

In the meantime, we are challenged to make “sense” of them as historical documents, texts, scripts, contests between discourses, administrative/medical records, narratives, and performances. We have drawn from theories and approaches in the humanities that foreground these qualities in the records. Our goal is not to provide a definitive interpretation or analysis or to explain the diagnosis assigned to a particular patient. Rather, it is to suggest some frameworks within which the phenomenon of the interview might be better understood.

I have chosen the interview of one patient from 1917 as a case instance. I could have chosen any number of others, and I make no claims for either its typicality or its singularity.

Betsy Jones (not her real name) was twenty-five years old when she was admitted to what would become Dix Hospital. She came from generations of farmers in eastern North Carolina. She married at the age of sixteen to a railroad agent. At the time of admission she had two children, the second born less than two months prior. The supposed causes of her being admitted were listed as “childbirth and heredity.” Manifestations of her illness were listed as talking continuously and not “noticing” children.

Her interview took place fifty-five days after her admission. Dr. W. G. Jenkins began by reading her case history, presumably based on the general casebook form filled out at the time of her admission. Superintendent Albert Anderson and the hospital’s first clinical psychologist, A. S. Pendleton, questioned Mrs. Jones. The typescript of the exchange filled six double-spaced pages.

Over the past twenty-five years or so, a new field of study has emerged at the intersection of the humanities and medicine, known variously as medical humanities, health humanities, or, literature and humanities. In its theories and methodologies, health humanities has adapted approaches developed in literature, critical theory, cultural studies, ethnography, oral history, and related disciplines.

One focus of recent work in health humanities has been the application of literary theory to the patient record, medical case, or medical history. As Rita Charon puts it, “there is no magic in the application of literary terms to medicine, but there may be power in excavating the foundations of medical thinking and action that are thereby exposed. (“To Build a Case: Medical Histories as Traditions in Conflict,” Literature and Medicine 11:1 [Spring 1992]: p. 115) How might our understanding of the examination records that survive from Dix Hospital benefit from such a critical reading?

First, we can recognize the typescript of the examination as a text—a non-literary text, to be sure– but one to which critical approaches and terms can be applied productively. However, we are dealing with texts that resist being considered as instances of a familiar genre, either in medicine or literature. They are not medical case histories, although as noted above, they seem to presume a case history having already been prepared and known by whomever might read these texts. The structure resembles that of a dramatic script. The “actors” are identified and the text is a direct record of their spoken exchanges. The transcriptionist has attempted to render these exchanges as they were spoken and as they were heard at the time.

Dr. Anderson asks Mrs. Jones about being “torn up so much in your mind about, your mother being here”

A. Yes sir, I was studying about my mother and I was worrying because I wanted my papa to come and get her and he wouldn’t do it, and after I got nefvous (sic) and torn up, then he would do anything on earth to keep me from having to come here, said he would spend any amount of money on me to have me relieved.

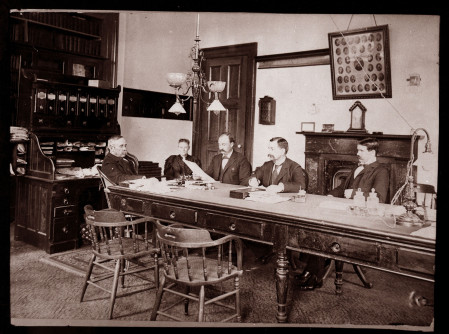

Performances are locatable in both time and space. The interview transcript does not indicate where it occurred or how the participants were arranged in relation to it and to each other. However, an undated photograph of the superintendent’s office might provide us with some idea of the place in which these examinations occurred in 1917. For example, the photograph shows the assembled doctors seated on one side of the table that takes up most of the space in the room, with a uniformed woman seated in the background. An empty chair is in the foreground of the image. Does this mean that the patient usually sat during the examination on the opposite side of the table? The one passage in the text referring to Mrs. Jones’s position in relation to Dr. Anderson suggests not only that she might have been standing but that she had to be instructed to face the doctors.

Q. Is there anything the matter with you?

A. Well, do you want to know?

Q. Yes, I want to know all about, turn around and tell all of the Doctors.

A. Do you want me to tell you what I was brought here for?

Close readings of other interview texts might reveal where patients were “supposed” to stand or sit as well as their compliance or resistance.

The resemblance of the text to a dramatic or cinematic script goes only so far, however. A script is a text that precedes its performance and was written to be enacted. It has an existence as text independent of any particular performance. The interview text is a record of this performance. It is contingent upon the circumstances—time, place, participants—of its spontaneous enactment. The script creates a self-referential world in which the performance occurs.

The surviving text constantly refers to the world beyond it and the “place” of the patient within that world. The words that are spoken are not only referential but consequential: what the doctors ask and what the patient replies can determine what happens next to the patient. Thus, perhaps the typescript more closely resembles a court transcript than a play. As Charon puts it: “. . .medicine offers to the literary critic an interesting case, a discourse that has direct and incontrovertible influence on events outside of itself. A close reading of the written and oral transactions of medicine rewards the critic with a textured anatomy of belief, power, and ontological fear in which the words themselves carry weight.” (Charon, p. 116)