Mrs. Jones uses the locution “torn up” to describe her feelings about her mother’s also being a patient at Dix and about her sister Pearl’s desire to come there to train as a nurse. Dr. Anderson asks her about her being “torn up so much in your mind,” and Mrs. Jones refers to a time “after I got torn up.”

The term survives as a colloquialism for being very upset about something. A 2019 Hollywood gossip column headline screams “SHE IS TORN UP!, explaining that “Bella Thorne is SO UPSET! Yes. Again. This poor girl needs therapy. Her ex is engaged and she is freaking out about it:( Sucks.” A Jacksonville, Florida, radio station website describes the godmother of a shooting victim as “torn up, broken-hearted and troubled.” The description of a soap opera episode reads: “Matt is made aware of Nikki’s changed behavior and the fact that she is torn up about her feelings.”

The locution I remember best growing up in Gastonia, North Carolina, is “tore up” usually preceded by “all,” as in the Cramps’ 1983 eponymous song:

I can’t hardly stand it

You’re troublin’ me

I can’t hardly stand

It just can’t be

Well, you don’t know, a-babe I love you so

You got me all tore up, all tore up

Green’s Dictionary of Slang defines it as “miserable, depressed,” with the first such use of either tore up or torn up cited in a 1887 North Dakota newspaper article. A second and more recent meaning of the term is given as “physically exhausted, very tired.”

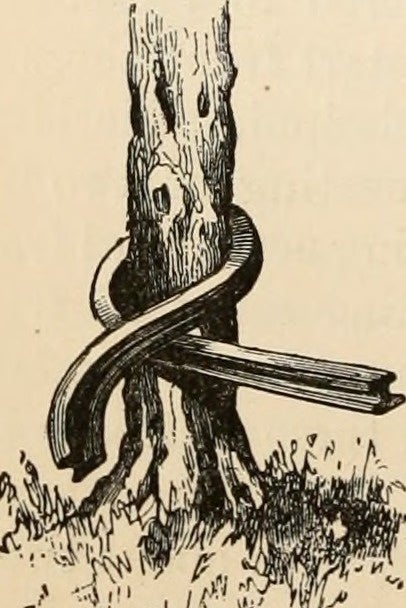

In the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century the term is used to characterize wide-spread damage and disorder, usually caused by a natural phenomenon. An account of a hurricane from the Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh) in 1724 reported that “Trees that stood exposed to the wind, were torn up by the roots.” Newspapers.com finds 32 instances of “torn up” in North Carolina newspapers in 1855.

Between 1861 and 1865, however, there were 575 instances of the term, most of them followed by “the tracks.” By 1860, railroads were essential means of transportation and communication across the country. They tied farms and villages to more urban centers, carried produce to markets and consumer goods and mail back to remote settlements. Telegraph lines were strung beside rail beds. Historian William Thomas argues that following the secession of the southern states, regional rail links were crucial in constructing a sense of nationhood for the Confederacy. Disrupting these rail-dependent social, economic, and political networks was an important part of the Union’s military strategy throughout the war.

In May of 1861, a member of the North Carolina legislature used the term as a part of his description of the apocalypse facing the South:

On yesterday we were a happy and prosperous people, commanding the admiration of the world. On to-day we are divided into two great hostile sections, and like the chafed viper stinging ourselves to death. Scenes are passing which give promise of the most terrific and blood drama the world has ever seen. Telegraph wires are broken; railroads torn up; ships burnt and sunk; forts stormed and taken; armories, arsenals and navy yards blown up, burnt, surrendered; blood is spilt, life is taken, and hundreds of thousands of men leap to arms as springs the tiger from his crouching. (Semi-Weekly Standard [Raleigh], May 4, 1861, p. 2).

As the war dragged on, civilians saw newspaper accounts of railroad tracks being torn up throughout the South as signs that the Confederacy could not be sustained. The systematic destruction of rail lines and stations was key to General William Sherman’s campaign in 1864 and 1865. Tearing up miles of track as his troops moved relentlessly through Georgia and the Carolinas not only prevented Southern commanders from repositioning their troops, it effectively isolated Southern cities, rendering them, in Sherman’s words “dead and worthless.” (William G. Thomas, The Iron Way: Railroads, the Civil War, and the Making of Modern America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011). So important were the railroads to Sherman’s campaign plans that in July 1864 he ordered his troops to shoot anyone who threatened the tracks.

In 1866, Newspapers.com shows only 42 instances of “torn up” in North Carolina newspapers, including this one in The Carolina Watchman (Salisbury, NC) in February: “Then the Confederate soldiers of the south and west, returning to their homes after the surrender, found the railroads torn up and burnt—footsore, weary, pennyless, disheartened, a long way from home, and believing the enemy would soon sweep the country of everything they themselves might leave behind. . . .” The apocalypse had indeed occurred.

By 1887 we do find the term “torn up” beginning to be used metaphorically to describe an individual or a group of people being upset or in serious disagreement over something of consequence. A family is England is described as “all torn up” over internal political differences. The residents of Scotsboro, Alabama, are “all torn up” by the revelation that a group of men were hanged on the basis of false testimony. A church in a small town is “all torn up” after thieves posing as ministers stole money from the congregation. The first comic use of the term I can find comes in 1890, in a humorous newspaper column. A husband tells his wife that if she hadn’t agreed to marry him she would have spent the rest of her life like a lottery ticket after the drawing: all torn up.

We find the term being used in a humorous/ironic sense to describe a home in disarray (all torn up) and in advertisements for early department stores having just received new shipments of goods, asking patrons to forgive their shop floors being temporarily “all torn up.” Both these uses of the term survive into my childhood in the 1950s. My mother would apologize to visitors for our house being “all torn up.” But she would also refer to shopping at Belks (a regional department store chain) as “tearing up some counters”—meaning that she didn’t intend (or have the money) to buy anything, but she wanted to go through what was on offer, disarranging the displays in the process. As a part-time clerk in at Belks throughout my high school years, I was regularly ordered to attend to “them tore up counters.” Thanks, Mom!

As North Carolina industrialized at the turn of the century through the construction of hundreds of cotton mills and tobacco factories, the term is applied to physical injuries, particularly involving limbs. In 1890 a man has his arm “torn up” by a cotton gin so badly that it has to be amputated, and a worker at a Durham tobacco factory has his hand “badly torn up.”

Overwhelmingly, however, the term and its variants continue to be applied to devastating damage to the natural or built environment and order: trees and crops (in the sense of uprooted), railroads, streetcar tracks, and (newly) paved streets. By the time of Mrs. Jones’s admission to Dix in January 1917, the term is regularly used to describe the destructive horror of another war, which has lasted almost as long as the American Civil War. In late December 1916, when Mrs. Jones is tending to her newborn daughter, newspaper headlines announce that fighting on the Somme front had been suspended for the winter: “Country Torn Up by Shells Impossible to Advance Over.” In a New Year’s sermon to his congregation in Salem, NC, a minister describes conditions in France where “The very air has become a horrid expanse where bombs have been dropped on the aged, the infirm, and helpless babies.” He mourns for fallen soldiers and their families but also for the fate of non-combatants “in torn up homes, in wandering multitudes, oppressed, beggared, starving and filled with sorrows.” (Charlotte Observer, Jan. 3, 1917)

What I am not trying to do here is to “explain” what Mrs. Jones meant when she described herself as torn up. Rather, I am demonstrating how millions of newspaper pages can be used to survey the discursive landscape within which this might have been understood and deployed by her. Certain words and phrases become freighted with associations and potential meaning over time, through constant use and circulation through communities. The use of “torn/tore up” to stand for destruction, disturbance, disorder, dislocation, disconnection, dispossession in the external world and its power to suggest an analog in the mental world were available to Mrs. Jones on March 24, 1917. She made a choice to use this term. It deserves as much attention from us as “Dementia Praecox and Exhaustion Infectious Psychosis.”